By Heather Wilson, Assistant Director for K-12 Learning

As we approach the 250th anniversary of the start of the Revolutionary War, we are excited to announce the launch of four new primary source sets on topics set in the 1770s on the History Source! We were thrilled to spend the summer working with scholars and K-12 teachers to breathe new life into these historical topics, and teachers can download all materials to use in their classrooms for free! These four new source sets were made possible with funding from the MA Society of the Cincinnati. Read on for a brief description of our new sets.

Investigating Multiple Perspectives on the Boston Massacre

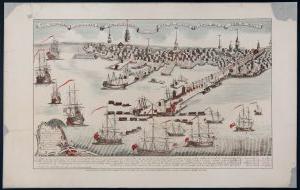

The arrival of British troops in Boston in the fall of 1768 – dispatched to protect customs officials tasked with collecting duties put in place by the Townshend Acts – is the catalyst for this primary source set on the Boston Massacre. With this context, students then analyze visual and written propaganda created in the wake of the night of 5 March 1770. Teaching activities use witness testimonies from a diverse array of Bostonians to help students understand that people’s accounts of that night conflicted with one another and could be influenced by their existing social relationships and politics.

The Evolving Legacy of Crispus Attucks: 1770-1863

According to a Boston newspaper a week after the Boston Massacre, Crispus Attucks, a Black and Indigenous formerly enslaved man, had been born in Framingham and was passing through Boston “in order to go for North Carolina” in his work as a sailor. Instead, Attucks was one of five victims killed by British soldiers on the night of 5 March 1770. Attucks’ role that night was contested. Some portrayed him as the instigator and leader, while others claimed he was merely a spectator. In his defense of the British soldiers, John Adams blamed Attucks for the Massacre, using only select witness testimony as evidence. In the mid-19th century, the Black abolitionist and historian William Cooper Nell revived the public memory of Attucks. Like Adams, he portrayed Attucks as the leader of the event, but in the heroic role of a martyr standing up against tyranny.

Attucks was not the only person of color present in the streets of Boston that fateful night, even though Revere’s famous engraving depicts only white people at the scene. Witness testimony and depositions from the trial of the soldiers also include the words of Andrew (last name once known), a literate man enslaved by a member of the Sons of Liberty, and Newton Prince, a free Black lemon merchant and pastry chef who ultimately left Boston for London as a Loyalist.

Boston 1773: Destruction of the Tea

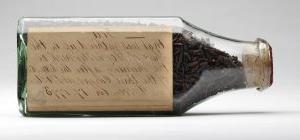

December 16th of this year marks the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party, or, as it was known at the time, the Destruction of the Tea. In this set, students explore broadsides, diary entries, artifacts, political cartoons, news articles and more to understand the wide variety of perspectives various stakeholders brought to the tea crisis. The set ends with the first three Coercive Acts, which Parliament enacted to punish and exert increased control over the rebellious colony.

Massachusetts Loyalists: Revolution and Exile

Following the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, British colonists in North America were proud to be part of such a vast empire. By 1775 – and following a series of protests against British tax policies – the first battles of the Revolutionary War had taken place in Massachusetts. However, not all colonists joined the Patriot cause. In this set, students explore who Loyalists were, why they maintained their allegiance to the British Crown, and what consequences they faced as a result.

Many thanks to: Kate Bowen, Abigail Portu, G. Patrick O’Brien, PhD, Ben Remillard, PhD, J.L. Bell, and Serena Zabin, PhD, for their work as writing consultants and/or scholarly advisors on these source sets!

Check out all four sets on the History Source!