By Miriam Liebman, Adams Papers

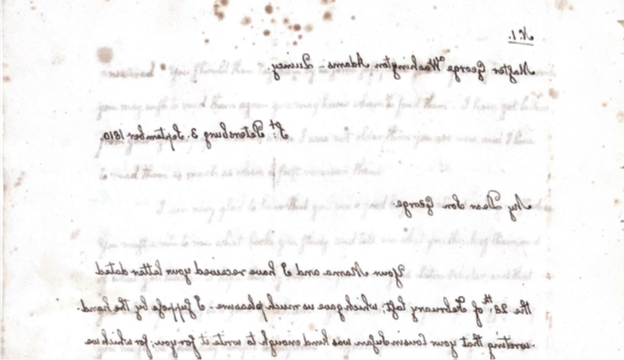

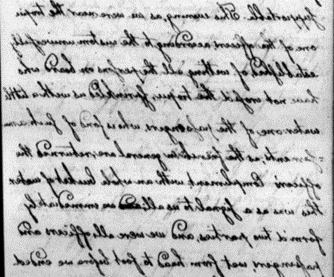

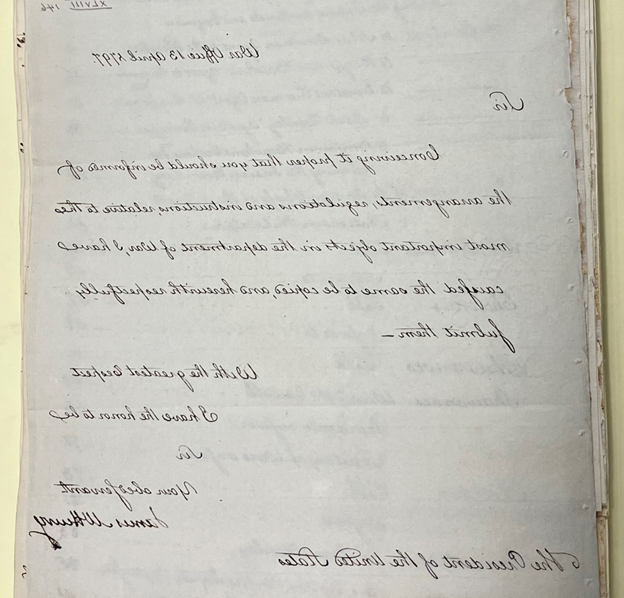

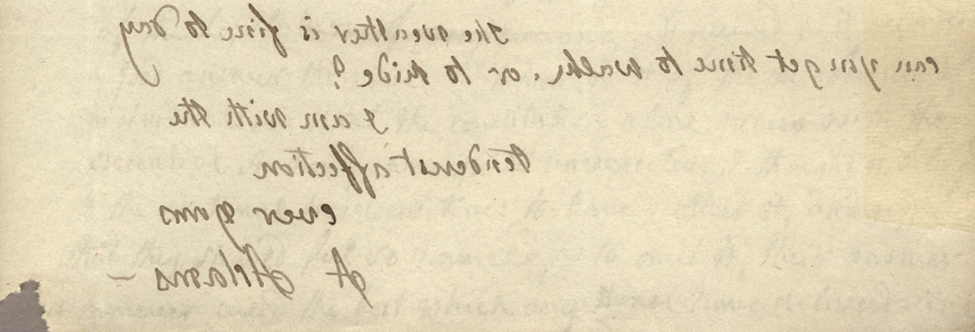

For the upcoming Papers of John Adams, vol. 24, I have been working to identify a group of women who sent Pres. John Adams a petition in 1799 or 1800 (the exact date still needs to be further researched; maybe I will discuss the process of redating documents in a future post!). These 72 women wrote this petition on behalf of men charged with crimes of “sedition and misdemeanors” for their participation in Fries’ Rebellion in March 1799. The rebellion started in resistance to a new federal tax law and other federal laws including the Alien and Sedition Acts. If you are interested in reading the whole petition alongside the women’s signatures, it is available on the American Philosophical Society’s website. The women wrote as “mothers and wives petitioning for fathers for husbands and for children” acknowledging that while it was uncommon for women to send such a political petition in their position as mothers and as wives they were not “overstepping” their role. In many ways, they embodied the ideal of Republican Motherhood, which you can read more about in my last blog post.

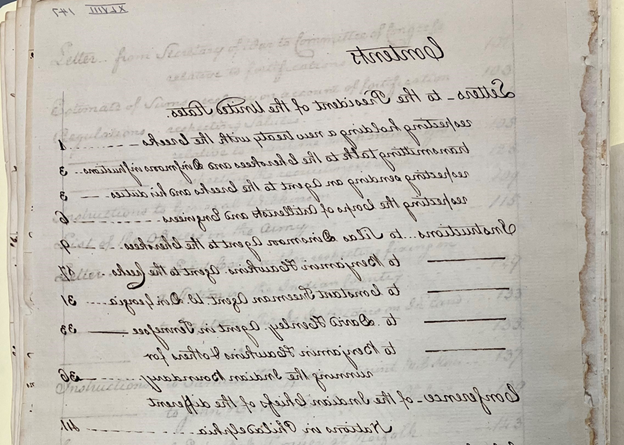

While the petition does not contain the names of the men, we do learn that these women wrote on behalf of more than thirty men imprisoned in the “Gaol of Philadelphia.” General William MacPherson who led the federal forces against the rebellion returned to Philadelphia with 31 prisoners, who were potentially the subjects of this petition.[i] The text of the petition says that they included a list of the prisoners and their punishments, but that document did not seem to survive. They asked John Adams to pardon the prisoners for their crimes, sentences, and fines.

This document is unique in that it is signed by over seventy women, whose names often do not make the history books. Over the past few months, I have started the process of identifying these women and what brought them together to write and sign this petition.

Searching for these women in traditional sources has proved challenging for a number of reasons. First, women’s names were often not recorded in censuses or city directories in the late eighteenth century, unless they were widows. Second, for birth and death records, I need to account for whether the women were married or single at the time they signed this petition. Most married women changed their last name when they got married. My strategy has been to start with the more unique names since I have a greater chance of identifying them.

For example, one of the petitioners signed her name “E. Vredenburgh.” While she did not provide her first name, her last name seemed unique enough that a limited number of results would appear when searching her name. I first searched the Philadelphia Directory for both 1799 and 1800. While she did not appear in either directory, someone named Isaac Vredenburgh was listed at 74 Market Street. I then searched newspapers to see if she was mentioned anywhere. There was an advertisement in the Philadelphia Dunlap’s Daily Advertiser, 19 September 1795, announcing that she was moving her shop from one address to 74 Market Street and provided her first name, Esther. Now that I had her first name, I turned to Ancestry.com to see if I could find out more about her. Isaac Vredenburgh’s will, which was on the website, listed Esther as his wife. I was also able to locate her grave on Ancestry.com and found out she died on 25 July 1810. These are some of the most helpful sources when trying to confirm the identity of these women. I am still trying to figure out how this petition came to be and how it brought this group of women together.

As I was finishing up this blog post, I came across another blog post from the American Philosophical Society on this petition and their journey identifying these women. Hopefully between these two projects, we will successfully be able to identify all 72 women and give them their place in the history books.

I hope to update you all here in a few months where my research has taken me and how much more I have learned about these women.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.

[i]Newman, Paul Douglas, “The Federalists’ Cold War: The Fries Rebellion, National Security, and the State, 1787–1800,” Pennsylvania History 67 (Winter 2000), p. 29.