by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

I’m very happy to add a brief postscript to last year’s seven-part series about Civil War soldier Dwight Emerson Armstrong. Last fall, following on the heels of that series, the MHS acquired the letters of his brother, Joel Mason Armstrong.

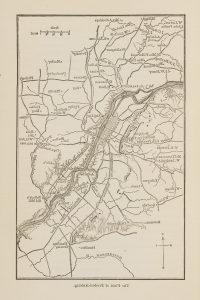

Mason (as he was called) was born in 1833 in Wendell, Mass. He worked as a carpenter in Sunderland before enlisting at the age of 28. He would serve for almost a year in the 52nd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Co. G., primarily in Louisiana. His collection is even smaller than his younger brother Dwight’s, but no less interesting. It consists of seven letters: six from Mason and one to Mason from none other than Dwight himself.

Dwight’s letter was written from Washington, D.C. on 15 September 1861, early in his service and before he’d seen any fighting. In it, Dwight described the building of batteries, the sound of nearby skirmishes, and a review of the troops by Gen. McClellan. I wrote about this period in Part II of the series.

All six of Mason’s letters were written to his sister Mary—the same sister, incidentally, to whom Dwight wrote his letters. Mason included some terrific details about life in the Union army, from the looting of nearby plantations for poultry, sweet potatoes, and sugar, to the days spent marching (“I find that I can tire out almost every one else & then march some ways further.”), to the thousands of formerly enslaved people who joined the Union caravan in the months after the Emancipation Proclamation. As for insight into Mason’s personality, I think this quotation sums it up: “I made up my mind long ago to make the best of everything and bear cheerfully whatever comes that cannot be helped.”

This collection also contains the letter Mason wrote to Mary on learning of Dwight’s death. Dwight was killed in battle on 3 May 1863, but Mason didn’t hear about it until nearly a month later, on the morning of the 29th. The news was confirmed by that day’s mail.

I Hoped that it was not so, until I got your letter & others telling the same story. I had not heard from him for a long time & began to feel anxious since we heard of the battle. It is indeed a sad blow to us. It seems hard to friends at home to think of dying so far away from home & friends; judging from my own feelings I think it is harder for friends at home than for those who die.

This patchwork of related collections is one of the advantages of a manuscript library like the MHS. Multi-generational papers, papers of different family branches, friends and neighbors running in the same social circles, letters from soldiers serving in the same military unit, travelers crossing each other’s paths—all of this overlapping and complementary material gives us a fuller picture of historical events and an opportunity to view those events from different perspectives. It’s not unusual to be working on a collection and run across the name of a person whose papers you recently processed.

I found biographical information about Joel Mason Armstrong in History of the Town of Sunderland, Massachusetts (pp. 254-5) and A Record of Sunderland in the Civil War (p. 14). The latter even confirms his aforementioned proficiency at marching! But these two sources don’t include one interesting personal detail that I turned up.

Mason and his wife Helen had seven children, but one online source contained what I initially took to be a mistake. Listed among his children was Clara I. Sweetser, but she was born a year before their marriage. A child from a previous marriage perhaps? The name rang a bell, so I looked back at my genealogical research from last year.

Sure enough, Sweetser was the married name of Mason’s oldest sister Sarah. Sarah and her husband both died in November 1864, just six days apart from each other. They left five children, the oldest only 14. After a little more digging, I found that six-year-old Clara, their only daughter, was in fact raised by Mason and Helen. (I couldn’t confirm it, but I assume her brothers were raised by other family members.) Sources seem to conflict on whether she was formally adopted, but her name was legally changed to Armstrong in 1865. Clara would marry in 1883 and have four children of her own.

Joel Mason Armstrong died in 1905 in Sunderland, Mass.