By Heather Rockwood, Communications Manager

The recent argument that almost became a fistfight on the floor of the US Senate is not something new. There have been many political arguments that have resulted in duels, fistfights, and beatings among elected and appointed officials, as well as among political activists.

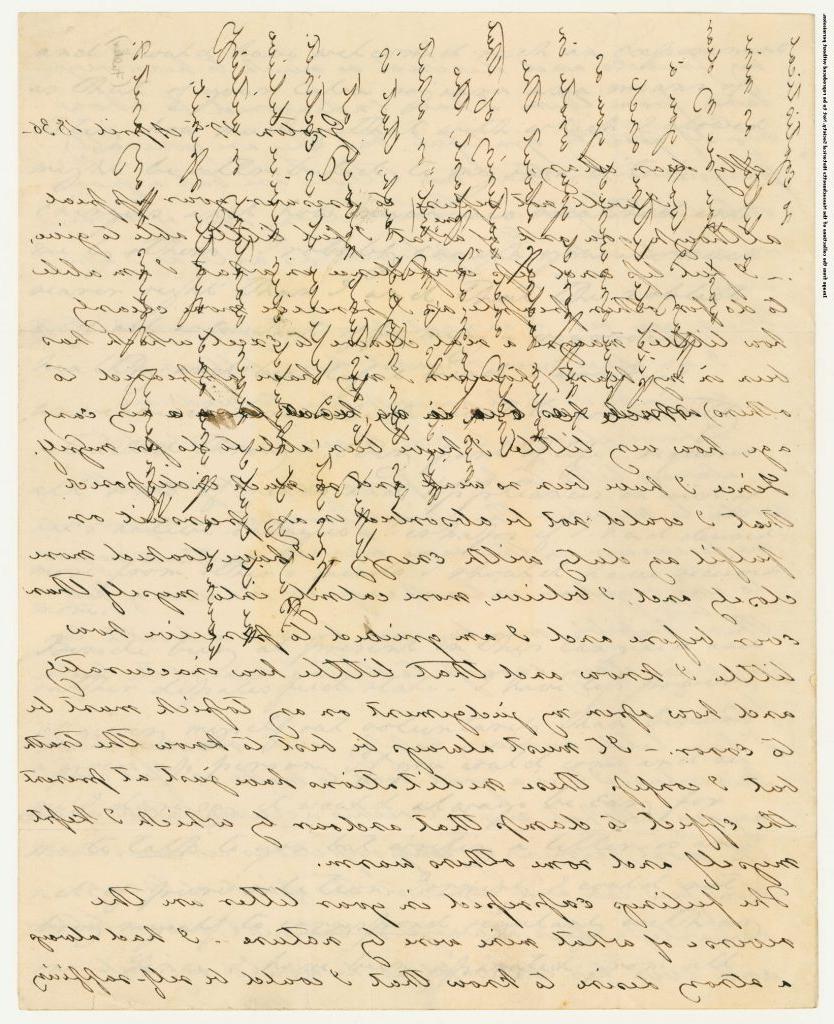

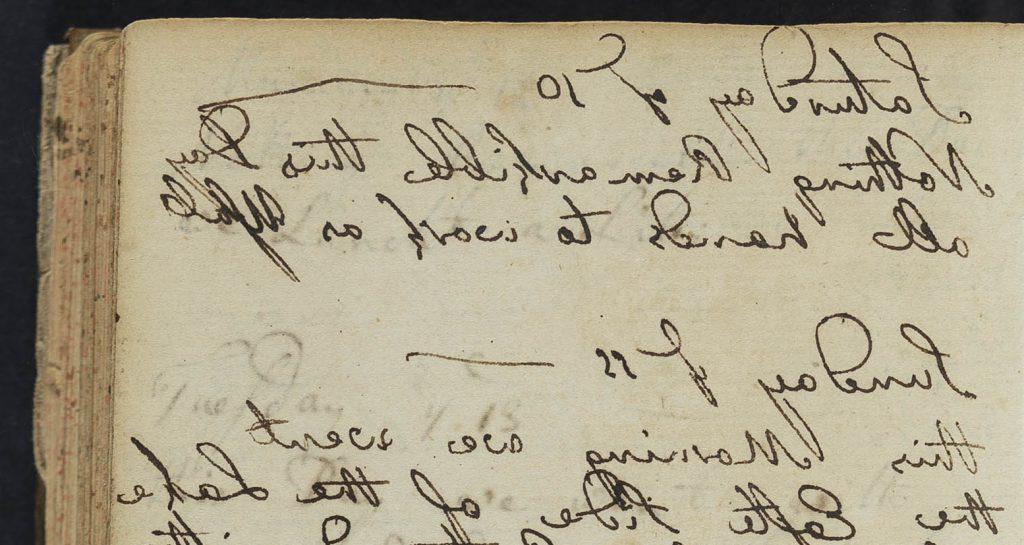

One occurrence is recorded in a letter from Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (1850–1924) to Theodore Roosevelt, 4 April 1917. Lodge decided against meeting with a group of pacifists who wanted to keep the United States out of WWI, while he himself supported US intervention. However, he did step outside of his office to speak with them. They exchanged insults, and then blows. He described the scuffle in his letter:

The pacifist crowd I went out in the corridor to speak with was composed of one woman and half a dozen men. They were very violent and very abusive and I was engaged in backing away from them and saying that we must agree to differ when the German member of their party said “You are a damned coward”. I walked up tp hit and said “You are a damned liar” and he hit me and I hit him. Then all the pacifists rushed at me and I thought I was in for a bad time buy my secretaries sallied forth to my rescue and there was a mixup. The pacifist who attacked me got badly beaten up and it all ended very comfortably and without hurt to me. At my age (66) there is a certain aspect of folly about the whole thing and yet I am glad that I hit him.

What occurred next was that the leader of the pacifists, a 36-year-old Alexander Bannwart was arrested, and Lodge became an abashed national celebrity. He continued in his letter:

The Senators all appeared to be perfectly delighted with my having [hit him] and some of them told me today that the further one went from Washington the more complete my action seemed. Watson [James E. Watson (1864–1948) Senator from Indiana] said that in Indiana the general belief was, he gathered, that I had beaten him to a pulp and that when one got across the Mississippi the general belief probably was that I had killed him, – all of which for the moment has made me extremely popular.

Lodge did not press charges against Bannwart, however a year later Bannwart pressed charges against Lodge for slander. Lodge settled by acknowledging that he punched Bannwart first, thereby starting the fight, although by his own hand above, his story, at first, was that Bannwart was the instigator.

The most famous attack on the Senate floor occurred on 22 May 1856. Senator Charles Sumner, (1811–1874), an abolitionist, had given a speech two days before, in which he insulted Representative Preston Brooks’s first cousin, Senator Andrew Butler, who had coauthored the legislation that would bring Kansas into the country as an state allowing enslavement. Brooks attacked Sumner, beating him brutally with his cane, which eventually broke. Even after Sumner had lost consciousness, Brooks kept beating him. Although other senators tried to help Sumner, a Brooks ally prevented them by brandishing a pistol. After the assault, Brooks walked away, leaving the remnants of his cane. He was arrested, tried, convicted, and fined $300 but never spent time in jail. His constituents reelected him that same year, and he spent much of his remaining lifetime making threats of duels and accepting duels that never took place. He died in 1857 of croup before his new term could begin.

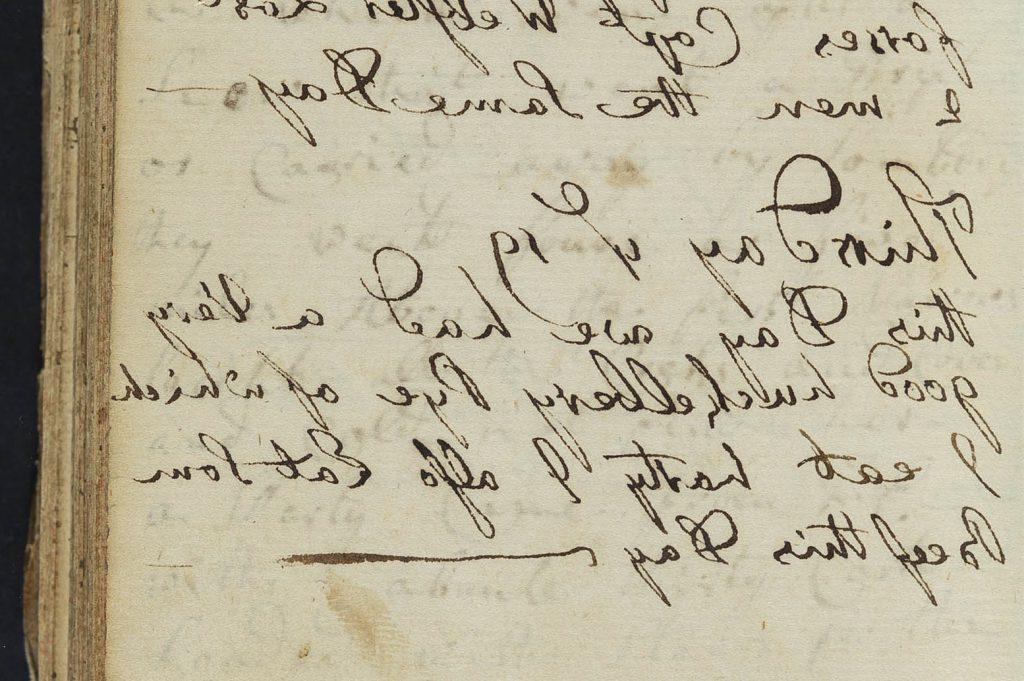

Brooks’s attack demonstrated the political polarization in the United States. In the north, Sumner was a martyr, in the south, Brooks was a hero. Sumner’s speech insulting Brooks’s cousin was printed and distributed; Brooks was sent canes to replace his broken one, the remnants of which went on to have two distinct lives. The bottom part was cut into small pieces that Senators sympathetic to Brooks wore around their necks. The top part was eventually donated to Revolutionary Spaces in Boston, and can be viewed here.

Although Sumner was reelected in November 1856, he spent three years away in recovery, his empty chair a symbol and reminder of the assault. He would later be diagnosed with “psychic wounds”—today’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—and severe brain injury, for which he suffered lifelong pain. He returned to the senate in 1859 and gave his first speech in 1860—appropriately, against enslavement.

Despite Sumner’s importance as a Massachusetts senator and his national political status, the collection of his papers at the MHS is surprisingly small. The reason for the shortage is political and personal. Sumner had a lengthy and bitter political feud with his boyhood classmate from the Boston Latin School, Robert C. Winthrop, who was the MHS president from 1855 to 1885. They had disagreed over the Mexican American War (1846–1848), causing Winthrop to block Sumner from becoming an MHS Member. The two enemies eventually reconciled in 1873, the year before Sumner’s death.